Saturday, June 09, 2007

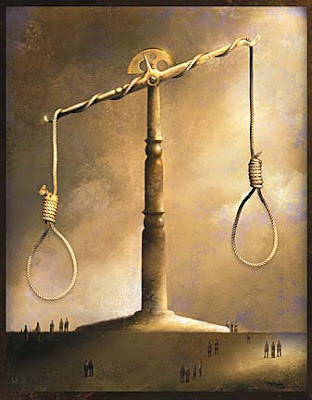

Supreme Court Ruling Will Mandate More Hard-Liners on Capital Case Juries

A decision by the Supreme Court on Monday that made it easier for prosecutors to exclude people who express reservations about the death penalty from capital juries will make the panels whiter and more conviction-prone, experts in law and psychology said this week.

The jurors who remain after people with moral objections to imposing the death penalty are weeded out, studies uniformly show, are significantly more likely to vote to find defendants guilty than jurors as a whole.

It has long been the law in every state with capital punishment that only people who are prepared to apply the death penalty may serve on capital juries. Monday's decision, which involved a juror's equivocation about the death penalty on learning that life without parole was an option, has the potential to make capital juries even less representative.

"It could give judges the authority to exclude about half the population from service in death penalty cases," said Samuel R. Gross, a law professor at the University of Michigan. That is because support for the death penalty drops from more than 60 percent to about half when life in prison is the alternative.

Even before Monday's decision, a significant minority of Americans were ineligible to serve as jurors in death penalty cases. According to a poll to be released today by the Death Penalty Information Center, a nonprofit group in Washington that is critical of the death penalty as currently applied, 39 percent of Americans say they have a moral objection to the death penalty that would disqualify them from serving in a capital case. The poll's margin of sampling error was plus or minus three percentage points.

Most of the research in this area is conducted by people and groups opposed to the death penalty. But prosecutors do not dispute the finding that capital juries are more apt to convict, arguing instead about the magnitude of the effect.

In a series of recent cases, the Supreme Court has narrowed the availability of the death penalty, barring its use on the mentally retarded and juvenile offenders, and has overturned death sentences based on flawed jury instructions, racial bias in choosing jurors and defense lawyers' incompetence.

Some death penalty opponents found it hard to reconcile those cases with Monday’s decision on the jury selection process that lawyers call death qualification.

"We may have a line of jurisprudence that is at war with itself," said Eric M. Freedman, a law professor at Hofstra University. "You can't simultaneously keep expanding the bounds of death qualification and also manifest a special concern for innocence in capital cases. As a brute matter of statistics, the farther you go in death qualification, the more wrongful convictions you will get."

Prosecutors say that death qualification is a necessary and narrowly tailored requirement that prevents only people who are unable to follow the law from serving as jurors. ...

(Joshua Marquis, the district attorney in Clatsop County, Ore., and a vice president of the National District Attorneys Association) conceded that the process of excluding opponents of the death penalty also conferred an advantage on prosecutors.

"I won't deny," he said, "that a death-qualified juror is probably more likely to be willing to look at a guilty verdict. I think that the difference is negligible."

Robert Blecker, a professor at New York Law School who supports the death penalty, agreed that "death-qualified jurors are slightly more conviction prone" than people opposed to the death penalty in all circumstances, whom he referred to as abolitionists.

"It makes sense and is consistent with human nature that abolitionists as a class are more pro-defendant in general and less willing to convict," Professor Blecker said. But the many safeguards in the system, he said, outweigh that slight distorting effect. "On balance, the system is, as it should be, skewed to prefer sentencing to life those who really deserve to die, rather than condemning those who deserve to live."

Jurors eligible to serve in capital cases are "demographically unique," said Brooke Butler, who teaches psychology at the University of South Florida. Professor Butler has interviewed more than 2,000 potential jurors over the past seven years and has written several articles on the topic.

"They tend to be white," she said. "They tend to be male. They tend to be moderately well-educated -- high school or maybe a little college. They tend to be politically conservative -- Republican. They tend to be Christian -- Catholic or Protestant. They tend to be middle socioeconomic status -- maybe $30,000 or $40,000" in annual income.

In a study to be published in Behavioral Sciences and the Law, a peer-reviewed journal, Professor Butler made an additional finding. "Death-qualified jurors," she said, "are more likely to be prejudiced -- to be racist, sexist and homophobic."

A 2001 study in The University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law, drawing on interviews with 1,155 capital jurors from 340 trials in 14 states, found that race played an important role in the willingness of jurors to impose death sentences.

In cases involving black defendants and white victims, for instance, the presence of five or more white men on the jury made a 40 percentage point difference in the likelihood that a death sentence would be imposed. The presence of a single black male juror had an opposite effect, reducing the likelihood of a death sentence to 43 percent from 72 percent.